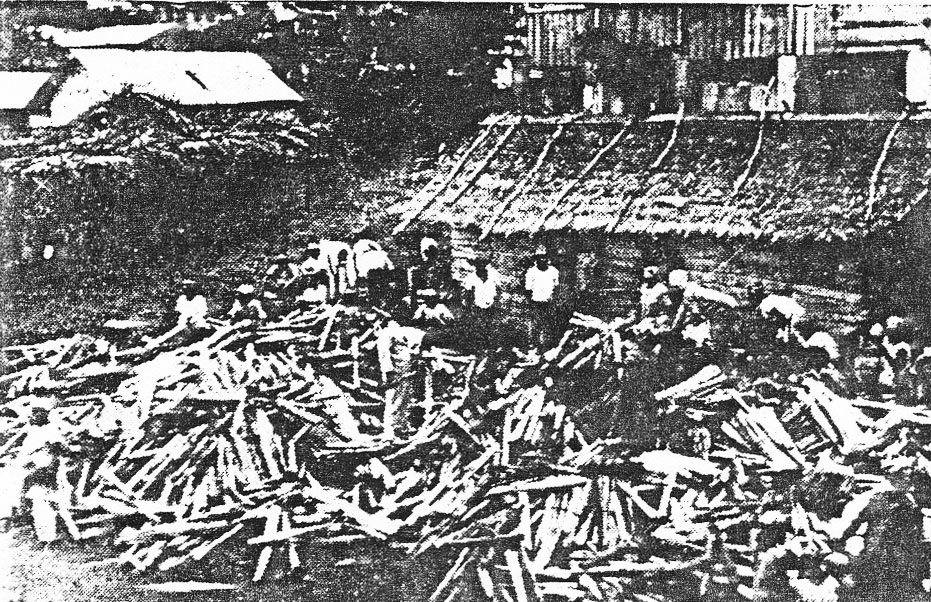

Plentiful firewood is given as a kindness to a Bubi woman who has given birth .

Plentiful firewood is given as a kindness to a Bubi woman who has given birth .

(From The Bubis on Fernando Poo)

Chapters 12 to 14: Women, birth, puberty

12. Condition of the Bubi Woman

In times past, a Bubi woman was condemned to be man’s perpetual slave and act as his beast of burden. Although in her infancy and first years of adolescence she enjoyed entertainment and the delight of her young state, much too soon she was seen as enough grown with sufficient strength to be put to hard work, at times more than her strength allowed. Here is the reason one finds, even today, a certain aire propios of the stronger sex in some places of the island.

Of those of us who have lived a long time in the colony, who has not seen the caravans of children, young maidens, and women arriving at the beach carrying large, heavy loads of yams and palm oil. They return to their besé (village) the same way, carrying cargoes of salt and other articles purchased from the bapotó. They are led by a man with his walking stick perched on his shoulder, like a muleteer with his herd, who arrives at his house tranquil and temperate, as if there were nothing to it.

When the women arrive at their village, they should do nothing but rest, even if they had been carrying less weight under less difficult conditions. However, quite the opposite happens. They arrive home from the beach sweating and worn out, yet everyone understands that a day at the beach is no treat for Bubi women. Now they must transport water and firewood. Of these two things, the water in particular is usually quite remote from their homes. They immediately begin to cook food for their husband and children, then set about making the ointment peculiar to them called ntola or ndola, with which they must anoint their husbands before they retire for the night. While the woman is busy in these chores, the man goes for a walk, or to obtain some exquisite palm wine, or to entertain himself with his companions talking in the boecha or boencha, which is “meeting house.”

The woman similarly helps her husband in field work. After finishing her daily tasks, she returns to the house with a heavy bundle of firewood or a giant bowl filled with yams, malangas or plantains, or different types of their good and flavorful edible plants.

In making palm oil, the Bubi men remove the cuttings and clear any remaining debris from the olives and pulp, but the rest of the operation is the women’s responsibility. The women must also secure the planting, cultivation, gathering, and storage of the malanga.

13. Birth and Infancy

As soon as a woman has given birth, all of her relatives, friends, and close neighbors are required to serve her. Some supply water to the new mother, others obtain firewood, others provide yams, malangas and other edibles, and still others stay in her house to prepare her food and care for the newborn and mother. This solicitous care of mother and child lasts while the mother lacks sufficient strength to do her ordinary domestic chores. While she is in seclusion, she receives many visitors, all offering congratulations, presenting small gifts, and showering blessings on the child and mother. Each visitor gives the newborn a name that, to him, appears to go best with the infant’s characteristics or future outstanding deeds, which, as time goes on, will distinguish him, and make him outstanding among his countrymen.

When the birth is twins, the family and neighborhood’s enthusiasm and joy increase. Then they aren’t satisfied with offering merely small gifts to the mother, as she is a person so dear and favored by the family spirits, but prefer to give her goat kids and lambs. They consider twins one of the biggest exceptional favors received from their ancestors.

About one week after a birth, they celebrate a modest feast. The family takes the newborn out of the house to ask the medicine man or prophet, mojiammó, which member of the family’s deceased bought its soul. Obtaining the answer, they give the child the name of his purchaser, who will be his protector and patron during his mortal life. This is the reason the same names repeat throughout the branches of family trees — one ancestor purchased all the souls. The naming complete, they celebrate a warm and joyful family feast.

It is general belief among the Bubis that God, himself, creates men’s souls, but when a woman conceives and God makes the soul of the fetus, a morimó, or deceased member of the family of the woman’s spouse, presents himself to God and asks that he be allowed to buy that soul. God, as he is so good and generous, sells it for a very small price. From this moment, he loses all rights that he had to that recently created soul and passes it to be the inalienable property of the morimó who bought it. It is from this that the Bubis deny they have obligations to God, except to keep for him their true respect and reverential fear.

All of their duties and obligations are for the morimó who bought them, who, as owner and absolute and perpetual master, they must always serve. To him they will appeal in all their undertakings, prosperity and adversities, in health and sickness, in their profits and losses, and in all the principal acts of life. To him they will offer their gifts, libations, and sacrifices. And of him they will hope to receive their rewards, if they live in conformance with the laws and customs they received from their ancestors, and the punishment deserved if they fail in their duties to the same.

From this one can understand the reason the Bubis have continued to use the words baribó or barimó, and so often comes from their lips invocations such as: “Ala Baribó! Ela Baribó!” They never invoke the name of God or call on his help or aid, unless it is an extreme case, at which times even atheists will instinctively invoke God’s name. Whoever claimed that the Bubis are true atheists, in as much as one couldn’t find evidence of adoration of the Supreme Being, was totally incorrect. As we will see later, they acknowledge a Creator Being of the world of all the things and even of their own baribó or barimó.

The ancient Bubis were unfamiliar with circumcision, and it never crossed their mind to circumcise anyone. If today the majority of children are circumcised, it is from long and continual dealings with the Mendes, Timenes, Fulas and other bapoti. Those foreigners usually circumcise the Bubi children since the Bubis are not experts in this operation.

The Bubis, during the time a child is nursing, permit the woman complete freedom from her duties and obligations. This may continue until the infant can stand and begins to walk. If the husband, being a little drunk, or some other person asks something of her, she pretends ignorance, saying, N’ta la paha o bola a te eba (N); N’da la paha, o mona a te ema (S): “I cannot, my child still cannot stand.” The Bubi distinguish themselves with their extreme solicitude in raising children. As far as possible, they never leave them but for brief moments. They wash or bathe them once or twice a day and keep them clean and decent.

It is the general opinion among them that if the woman, while nursing and before she begins relations with her spouse, commits adultery, will remain permanently sterile as punishment for her crime. Hence, if a young woman who has given birth to some children suddenly stops conceiving, everyone assures that someone gave her kobo. That means she had committed adultery during the lactation of her last child before having renewed relations with her spouse and the barimó who granted her fertility has punished her with sterility.

How many quarrels I have witnessed between spouses for similar suspicions! The woman who has been given kobo is met with dishonor.

14. Puberty

Puberty usually manifests in the indigenous of Fernando Poo at age sixteen or seventeen in males, and at fourteen or fifteen in young women. There are a few instances of this occurring earlier, but more commonly some occur later.

Young men celebrate their entrance into puberty, in particular in the northern regions, in the following manner: The day arrives and the young man takes a bath, spreads himself with ntola pomade, then adorns himself with bipa and besori or mesorí (cords from palm leaves) and other items. Supplied with traveling calabashes of palm wine, he presents himself to the village botuku. He offers the botuku one of these filled with the exquisite and tasty liquor and the botuku receives the calabash with signs of gratitude.

The botuku then gives him a new name, with which from now on he must be recognized. With a certain ceremony, they accept him into the category of the village’s young men of marriageable age. He presents himself to the chief of the young men, botuku boa baseseppe, under whose orders he will be while he remains single. The botuku boa baseseppe convenes a general meeting of the single adults of the village, presents the new candidate to them, and they all welcome him and congratulate him for having arrived at this happy and joyful age, so fervently desired by the girls and the source of nostalgic regret and envy by the old people. Later, amicably, they finish the remaining calabashes of the delicious liquor.

In reference to the new name that now distinguishes the pubescent, we note that they call the name of the youth ilá ro baseseppe, and the name that he had before this age the ilá ro bola, or name of the child. In the future, no one who is younger or equal to his age may call him with his childhood name.

On one occasion, I encountered a man who was already the father of a family, whom I hadn’t seen in years since he left the school. Naturally, I called him by the name that he had as a boy, as I was ignorant of the name of his young manhood. Hearing my words, another young man of his same age, who was ignorant of the custom’s particulars, asked him: “How is it that Father calling you with the name of your infancy doesn’t make you mad, but if I call you with it you are indignant and angry?” Replied the adult: “The Father can call me with it because he is much older than I; he instructed me, educated, and baptized me, and you are simply an equal, not superior to me.”

The civilized Bubi have already stopped this triviality.

There are neither festivities nor particular ceremonies for girls entering puberty. As soon as a girl becomes capable, which they place at about fourteen to fifteen years, the parent lets her suitor know he may come for her as soon as he pleases.

The man, before taking his purchased spouse into his house, requires an inspection of the young lady to assure that she remains a virgin. This inspection is practiced in the villages on the north side of the island; in the south it is falling out of practice. In the south, they have another method to determine if the maiden still keeps her eótó, or virginity, which they claim to be more reliable. Both results are uncertain, because there is no certain sign of a “criminal” loss of virginity.

Two or three old women from both families take the responsibility of inspecting the girl. If from their inspection they deduce she still remains a virgin, the two families congratulate each other and heap blessings and praise on the girl; but if they confirm she has been violated, oh, the poor child! What sad and bitter days await her.

The Bubis, when they give a dowry to acquire a wife, strive expressly to buy the eótó, or virginity. A maiden who has lost her virginity, even if it has been taken violently, has lost all her value and beauty. Such esteem and value the Bubis of antiquity had for virginity!

They anoint the maiden virgin with ntola, or ndola, making whimsical decorations and figures on her entire body, adorning her with bipa, besori or mesorí and a thousand varieties of beads. Thus adorned and beautified, they take her to her parents, or those who stand in for them, at her spouse’s house. She will lodge in a hut joined to his, which they give the name of bula or buna, which is, forbid or forbidden, and in it she will live a certain amount of time depending on the district.

Her daily occupation in seclusion will be to eat well, be meticulous in her personal cleanliness and the adornment of her person, and cultivate a small garden of ntola, ndola. She may not leave without urgent necessity, nor move even a little ways from the hut, until the solemn appearance at her wedding. In this confinement her spouse visits her, and ordinarily she leaves pregnant. During this time, the spouse works without resting in procuring the necessities for the solemnity of the wedding.

(1) Upon the birth of a baby, it is placed at the feet of the woman’s husband, and if he lifts it from the ground, he is recognized as its father.

(2) ) Three tribes from the neighboring West African coastal areas of Sierra Leone and Cotê D’voire. -- Trans.